What Lies Beneath? Seeing prints their way.

This month’s blog is about the importance of seeing what isn’t there. Political prints often worked by hints and asides, gesturing towards things that they didn’t depict but which were nonetheless vital to their point. Contemporary viewers would have ‘gotten’ those things at first glance. They would have seen what wasn’t there because they were immersed in the same political moment, read the same newspapers, saw the same plays, and shared the same culture as the graphic satirist. But at a remove of centuries, we are a beat or more behind. Seeing prints as they were first seen requires us to uproot what lies beneath an image.

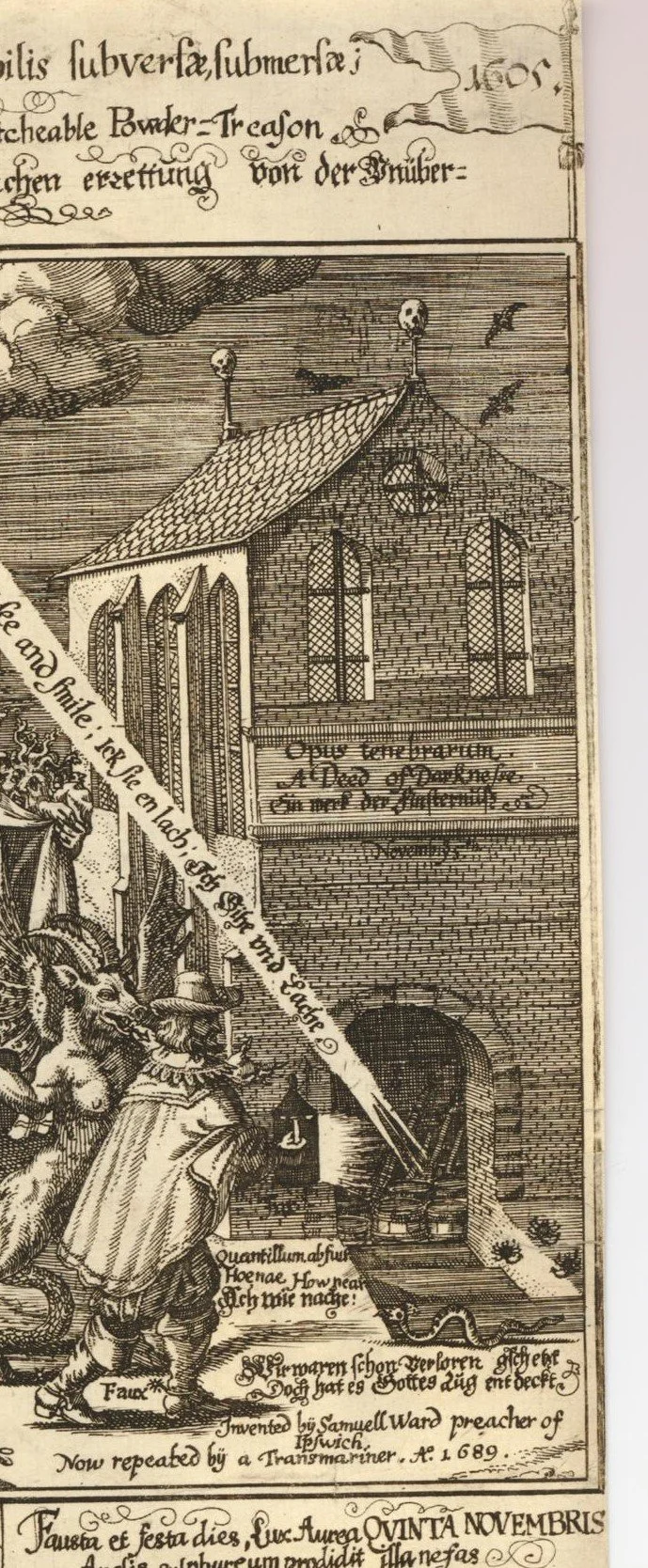

Figure. 1. The Papists Powder Treason (1689). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

I’ll explore this by examining The Papists Powder Treason [Figure. 1], an anti-Catholic print published during the 1688/9 Revolution that replaced the Catholic James VII/II with his Protestant daughter Mary II and her husband, William of Orange (who became William III). [1] The print was about the Revolution. But it didn’t portray that Revolution in its image or mention it in its text. Stirring the pot of public memory, The Papists Powder Treason used anti-Catholic imagery that had been part of the bric-a-brac of English Protestant culture for over 70 years to bring a host of unspoken associations to bear on the new political moment. The Revolution was celebrated without being pictured.

Figure 1 detail 1: The Armada scattered by the breath of God.

We must look at what was in the print before considering what wasn’t. The Papists Powder Treason portrayed the failure of the Spanish Armada (1588) and the Gunpowder Plot (1605) as providential deliverances from popery. In the centre Satan guides an unholy cabal of the pope, a cardinal, a Jesuit, and a friar in a conspiracy to destroy Protestant England. On the left, a crescent of Spanish warships was about to be scattered by an English fireship and ruined by storms sent by God to preserve the Reformation – Ventorum Ludibrium; I blow and scatter [detail. 1]. On the right, Guy Fawkes, instantly recognizable by his lantern, prepares to detonate the barrels of gunpowder hidden in the cellars of parliament, but was foiled by the laughing eyes of God – Video Rideo; I see and smile [detail. 2]. The imagery was simple, and so was the point. The antichristian forces of popery had long plotted to ruin England. Those forces were always foiled by providence. God therefore favoured England and its Protestant church.

Figure 1 detail 2: The Gunpowder Plot exposed by the eye of God.

This seemed uncontroversial: who could be against providence? The print looks like a treacly piece of commemorative tatt trading on the unthinking simplicity of commonplaces. But in 1689, The Papists Powder Treason’s anti-Catholic imagery was anything but uncontroversial. The implication was that William’s defeat of James was another deliverance from popery, and the print tied 1688/9 to a longstanding tradition of providential antipopery without ever saying or showing it. The closest we get is a nod and a wink: “Invented by Samuel Ward preacher of Ipswich/ Now repeated by a Transmariner. AD 1689” [2]. Repetition was the point. 1688 repeated 1605 which repeated 1588.

The Papists Powder Treason’s providential antipopery echoed the panegyric written to celebrate William III as England’s deliverer and to convince the public that the Revolution was legitimate and just [3]. The spin was necessary. 1688/9 was a national trauma involving an invasion, the humiliation of a king, an end to the Anglican Church’s monopoly on public religion, and the uprooting of long-held assumptions about monarchy, sovereignty, and the constitution [4]. Plotting 1688/9 in an anti-Catholic tradition spun the Revolution as a continuation of English history, not a departure from it. William’s defeat of James’s ‘Popery and Arbitrary Government’ was absorbed into the apocalyptic tradition of English history popularised by John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1563), which had presented the Tudor Reformations as a liberation from the papacy’s anti-Christian tyranny [5]. Revelation warned that Antichrist would rage against the godly in the end times. The papacy’s excommunication of Elizabeth I (1570), the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants in Paris (1572), the assassination of William of Orange (1584), the Armada (1588), Nine Years’ War in Ireland (1590s), the Gunpowder Plot (1605), the Spanish Match (1621-23), and massacre of Protestants in Ireland (1641) consequently developed into a litany of rages, ‘popish’ acts of aggression that proved history was unfolding to an apocalyptic schema in which Protestants would win the final victory [6]. Propagandists claimed 1688 as the next line of that litany. It became conventional for 5 November sermons in parishes across England to tie 5/11/1605 (deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot) to 5/11/1688 (William’s landing at Torbay to deliver England from James) and celebrate both as pivotal moments in the history of English liberty.

Our print was a visual rendering of that story. It was involved in a process of trying to use anti-popery to manufacture consent during a period of acute political crisis. The Revolution was no fait accompli. Its Whig ideals – toleration, constitutional monarchy, and a deep-set suspicion of clericalism – caused bitter divisions between Whigs and Tories, loyalists and Jacobites, and Anglicans and Dissenters that shaped national life into the mid-eighteenth century and which were magnified by the performative combativeness of England’s first age of party politics [7]. Selling the Revolution as a providential victory over popery was a rhetorical move that attempted to overpower objections. The Papists Powder Treason was a sleight of hand, appearing to be a mere memorial pointing to a groundswell of Protestant opinion, but in truth serving as a polemic that used antipopery to dull the edges of the Revolution. With text in English, Dutch, and German, this was a line that its artist/publisher wanted to push to an international audience [8].

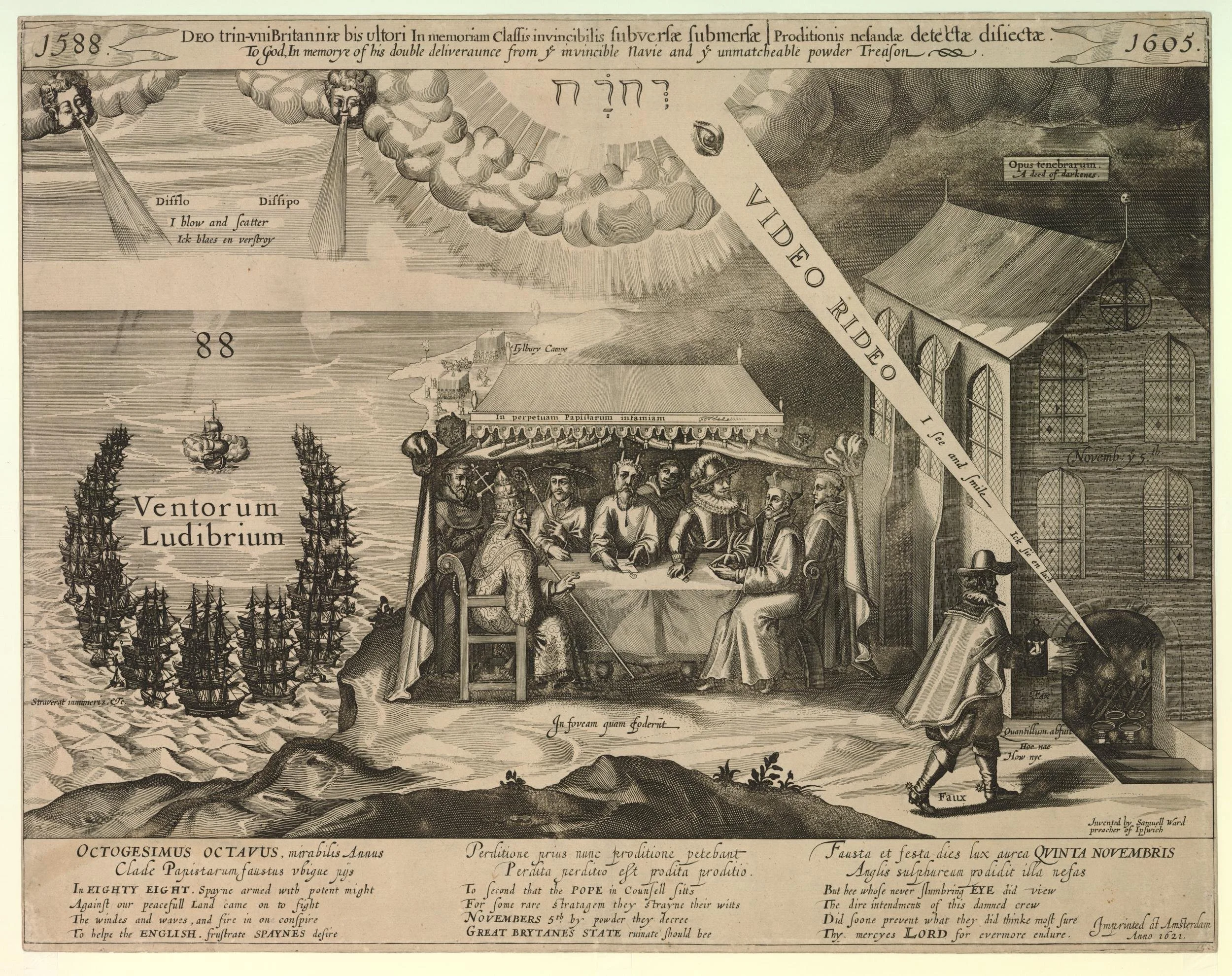

Figure 2: Samuel Ward, The Double Deliverance (1621). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

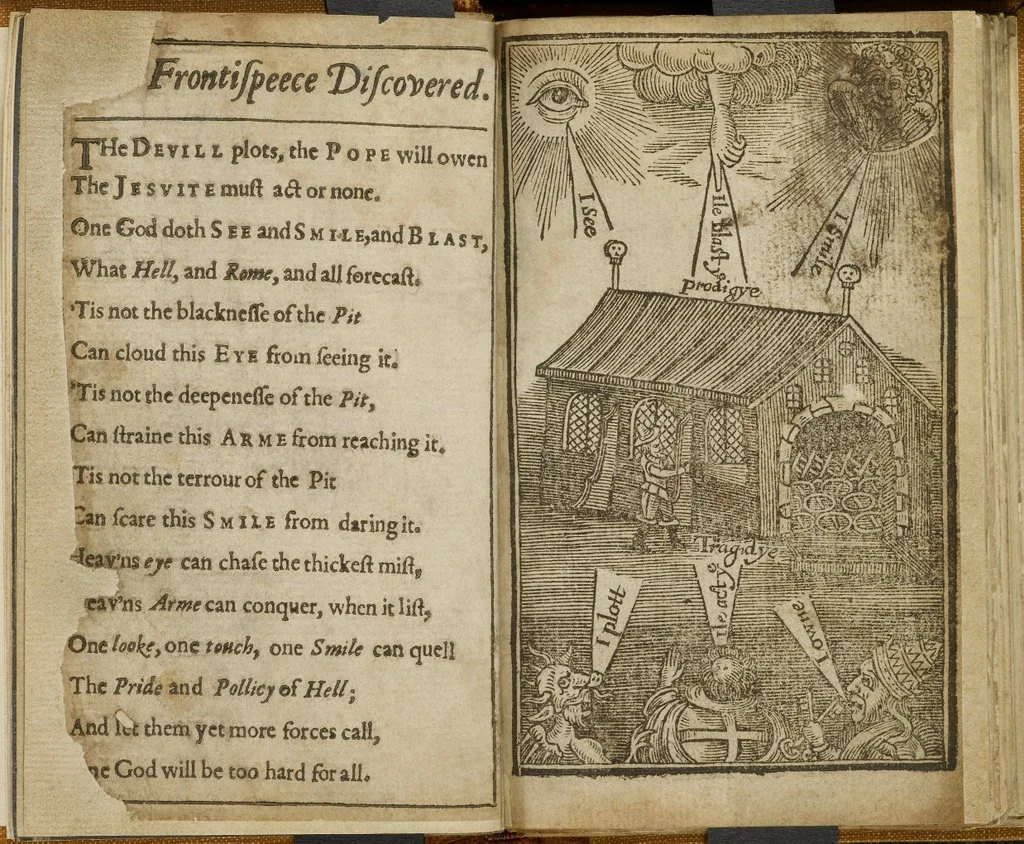

And yet the print is not as simple as that. The Papist Powder Treason’s imagery had a controversial history, a history that contemporary would have likely understood. The print was first published as The Double Deliverance by the puritan Samuel Ward in 1621, almost seven decades earlier [Figure. 2]. Ward’s print caused an uproar [9]. It offended the Spanish Ambassador at James VI/I’s court, Diego Sarmiento de Acuňa, count de Gondomar, whose objection caused Ward to be arrested for libel. Infamy led to The Double Deliverance being the most copied political print of the seventeenth century.

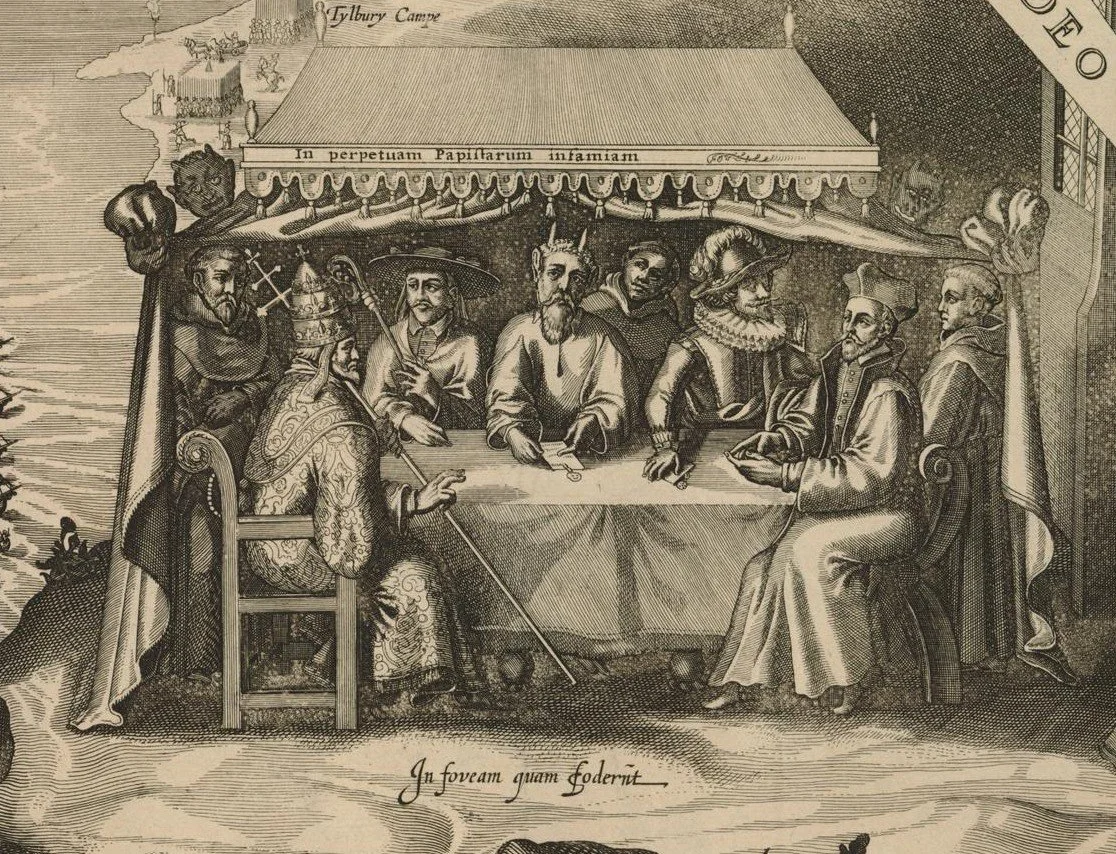

Figure 2 detail 1: The unholy conclave.

What was offensive about commemorating God’s providence? Gondomar’s complaint was with the cabal scene in the centre of The Double Deliverance, labelled ‘In perpetuam papistarum infamian’, which included King Philip III of Spain as one of the pope’s satanic co-conspirators [Fig 2.1]. Why Philip? In 1621 James VI/I was negotiating an alliance with Philip that would be sealed by the marriage of his son Charles to the Spanish Infanta. This ‘Spanish Match’ infuriated England’s hotter Protestants, already angered by James’s refusal to support Protestant Europe in the early stages of the 30 Years’ War, who accused the king of plotting to place ‘popery’ in the heart of the English state [10]. Ward rubbed on that sore. The Double Deliverance’s triptych presented the Spanish Match as another antichristian plot to undo Protestant England akin to the Armada and Gunpowder Plot. The difference was that while 1588 and 1605 the threats were foreign, in 1621 the English crown was complicit in the popish designs. The Double Deliverance used anti-popery as an anti-Stuart protest, suggesting that for a Protestant King to pursue the Spanish Match was a slap in the face of providence [11].

Figure. 3: The Papists Powder Treason (1679; original 1612). Permission of the Huntingdon Library, San Marino, California.

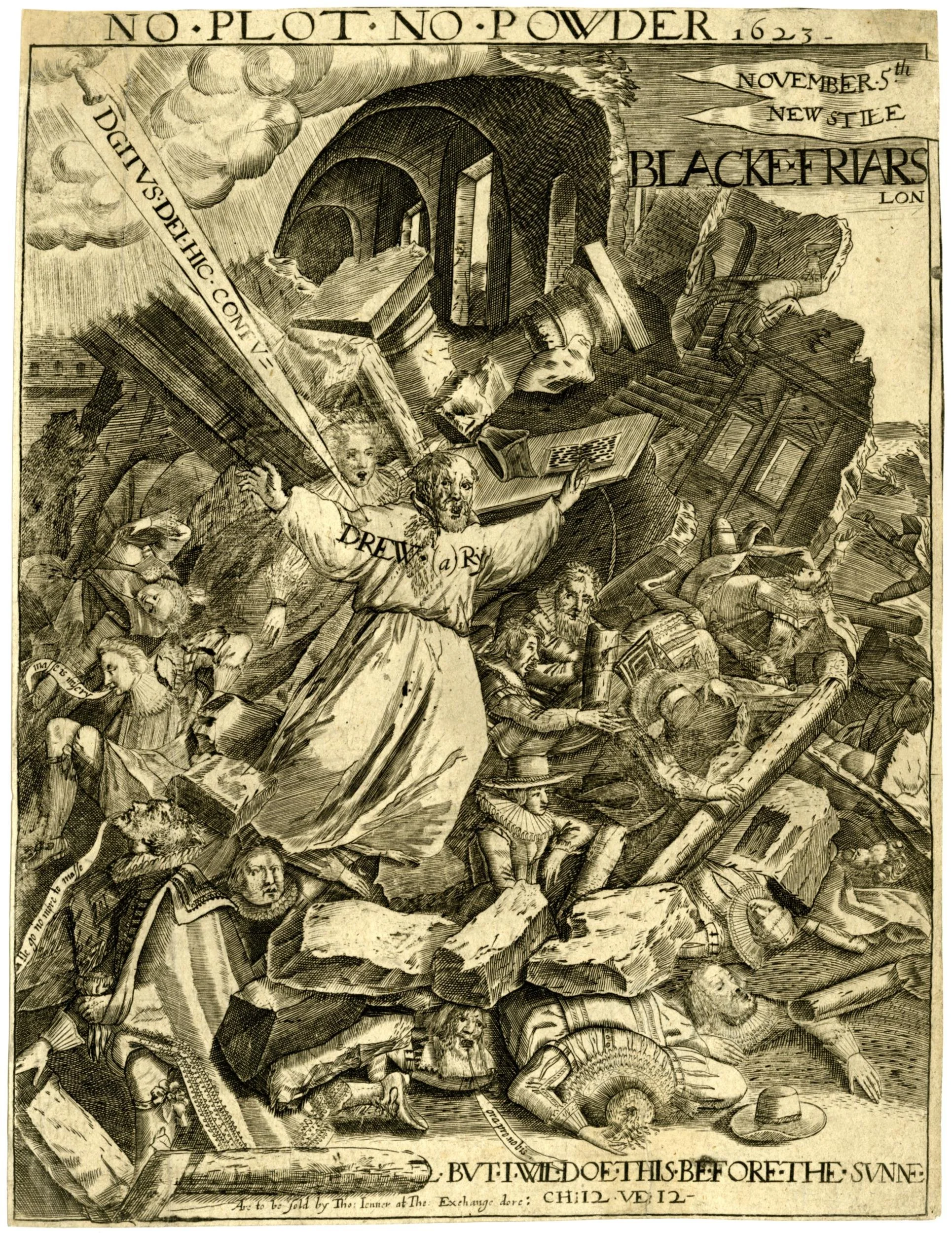

Figure. 4: No Plot No Powder (1623). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Ward denied everything, of course. No, that wasn’t Philip III. And no, the print was not a condemnation of the match but was exactly what it seemed – a memorial of two moments when God intervened to save England [12]. Ward’s defence was partially credible. By 1621 it was not unusual to produce prints as memorials to deliverance from popery. TITLE, for example, was an engraved monument to the Gunpowder Plot [Figure. 3] [13]. No Plot No Powder (1623) celebrated the collapse of an illicit Jesuit chapel in Blackfriars, which led to the death of 90 people [Figure. 4] [14]. But the reuse of The Double Deliverance’s iconography to protest against the Stuart crown across the seventeenth century suggests that Ward’s contemporaries knew exactly what he had intended. The Armada and Gunpowder Plot scenes were reproduced on the frontispiece of Christopher Lever’s, History of the Defenders of the Catholique Faith (1627), a call for James to be Europe’s Protestant Champion as the 30 Years’ War gathered pace [Figure. 5]. The frontispiece shows Elizabeth (bottom left) holding a banner showing the defeat of the Armada and James (bottom right) doing the same with the Gunpowder Plot. By the 1640s, these images were being used in publications attacking Charles I and Archbishop William Laud as agents of ‘popery and arbitrary government’ bent on subjecting England to tyranny and persecution [Figure. 6] [15].

Figure 5: Christopher Lever, History of the Defenders of the Catholique Faith (1627). Note also the scene at the top of Henry VIII trampling the papacy and other Catholic clergy under foot, a key theme of Tudor anti-Catholic iconography.

Figure 6: Novembris Monstrum (1641). Copyright of the British Library.

These associations were apparent in the reuse of the iconography during the Exclusion Crisis (1678-82), the attempt to prevent the Catholic heir to Charles II, James, Duke of York, from acceding to the throne. The Happy Instruments of England’s Preservation (1681) emulated central cabal scene of The Double Deliverance [Figure. 7] [16]. The print depicted the Popish Plot, a fictious conspiracy to murder Charles, massacre English Protestants, and place James on the throne that was fabricated by Titus Oates and elaborated by William Bedloe, Miles Prance, and other ‘witnesses’ who gave evidence against about the conspiracy that caused the death of over twenty Catholics in state trials. The Happy Instruments shows the witnesses seated below heaven, their ‘evidence’ guiding the eye of providence to expose the plot. The plot was used by the Whig party to add urgency to calls to prevent James becoming king and increase the powers of Parliament to ensure the safety of Protestant England. The Happy Instruments was published at a moment when the Whig party was lobbying for Charles to recall Parliament (which he had suspended because of its attempts to exclude James) to investigate the plot. The implication is that his reticence to do so (and to implement ‘Protestant’ reforms in the church and constitution) were proof of a conspiracy for ‘popery and arbitrary government’ within the crown.

Figure 7: The Happy Instruments of England’s Preservation (1681). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

When viewers saw The Papists Powder Treason eight years’ later, the anti-Stuart associations that its anti-Catholic iconography had accrued over the previous 70 years would have been apparent. That iconography placed the Revolution in a two-generations old battle against popery within England’s church and state. Reusing it in 1689 was to claim that the Revolution was an act of providence, and one which had delivered England from the Stuarts as much as it did from Rome. Not everyone was delivered equally. The print used the resonances of The Double Deliverance’s iconography to craft an interpretation of 1688/9 as victory for godly Protestantism and Whig politics.

Much lay beneath The Papists Powder Treason. The print masked its politics in the dress of commemoration, making its points by poking at narratives about England’s recent past by using anti-Catholic imagery that was popular, controversial, and a repository of Stuart England’s public memory. Memory rests on commonplaces. And commonplaces hide their politics by appearing to be more banal than they are. In The Papists Powder Treason two strands of memory collided in one iconography. The first strand evoked Protestant providentialism to tie 1688/9 to a much bigger story of Engand’s deliverance from ‘popery’ to try and fix how it would be remembered. Once plotted in this strand of memory, 1688/9 was not controversial, but a justifiable and divinely-sanction act in England’s history of escape from Catholic aggression. The second strand of memory evoked by the print’s imagery was opposition to the Stuart crown and church that unsettled English politics in the 1620s, the Civil Wars, and the Exclusion Crisis. For Whigs that opposition was a justifiable blast against the tyranny of ‘popery’ that was more at home than abroad; for Tories, it was a species of the seditious, enthusiastic, and anti-monarchism of popular puritanism that had destroyed the church and state during the Civil Wars and Republic. One of those strands of public memory dampened the controversial aspects of 1688. The other enflamed them. That The Papists Powder Treason could have referred to either speaks both to the fact that what contemporaries saw when they looked at prints was determined at the intersection of what the printed showed, what it left hidden, and the political leanings of the viewer.

[1]: British Museum: 1868,0808.3316.

[2]: The significance of the reference to Samuel Ward is discussed below.

[3]: Tony Claydon, William III and the Godly Revolution (Cambridge, 1996), PAGES.

[4]: For a superb account see Tim Harris, Revolution: the Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685-1720 (London, 2006); for an explanation of rival ideologies at work in 1688/9, see Steven Pincus, 1688: The First Modern Revolution (New Haven, 2008).

[5]: Tony Claydon, ‘Latitudinarianism and Apocalyptic History in the worldview of Gilbert Burnet, 1643-1715’, Historical Journal 51 (2008): 577-97; idem, The revolution in time: chronology, modernity, and 1688-1689 in England (Oxford, 2020).

[6]: See Adam Morton, ‘Glaring at Antichrist: Images of the Papacy in Early Modern England, 1530-1680’ (PhD Thesis University of York, 2011).

[7]: On the role of the press, see Mark Knights, Representation and Misrepresentation in later Stuart London: partisanship and political culture (Oxford, 2005).

[8]: There was, of course, international interest in 1688/9. There was also an international market of graphic satires on the subject. Romeyn De Hooghe, who was a propagandist for the House of Orange, published a series of satires on the events of 1688/9. See Meredith Hale, The Birth of Modern Satire: Romeyn de Hooghe and the Glorious Revolution (Oxford, 2020).

[9]: British Museum 1847,0723.11. For the response, see Helen Pierce, Unseemly Pictures (New Haven, 2010), 39-47.

[10]: See Thomas Cogswell, ‘England and the Spanish Match’ in Richard Cust and Ann Hughes eds., Conflict in early Stuart England (Houndmills, 1989). Gondomar also complained about a print of showing James VI/I holding the pope’s nose to the grindstone. This print has recently been discovered in a Spanish archive. See Helen Piece, TITLE.

[11]: Alexandra Walsham, Providence in Early Modern England (Oxford, 1999), 250-66.

[12]: The National Archives, Kew, SP 15/42/d; British Library, Harley MS 389 fol. 15.

[13]: Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. RB 28300 IV.21.

[14]: British Museum 1868,0808.3214. See Alexandra Walsham, ‘The Fatall Vesper: Providentialism and anti-popery in late-Stuart London’, Past and Present 144 (1994): 36-87.

[15]. On the reuse of the imagery, see Alexandra Walsham, ‘Impolitic Pictures: providence, history, and the iconography of Protestant nationhood in early-Stuart England’, Studies in Church History 33 (1997): 307-28.

[16]: British Museum 1848,0911.493.