Tee Hee He: Cruelty & Laughter.

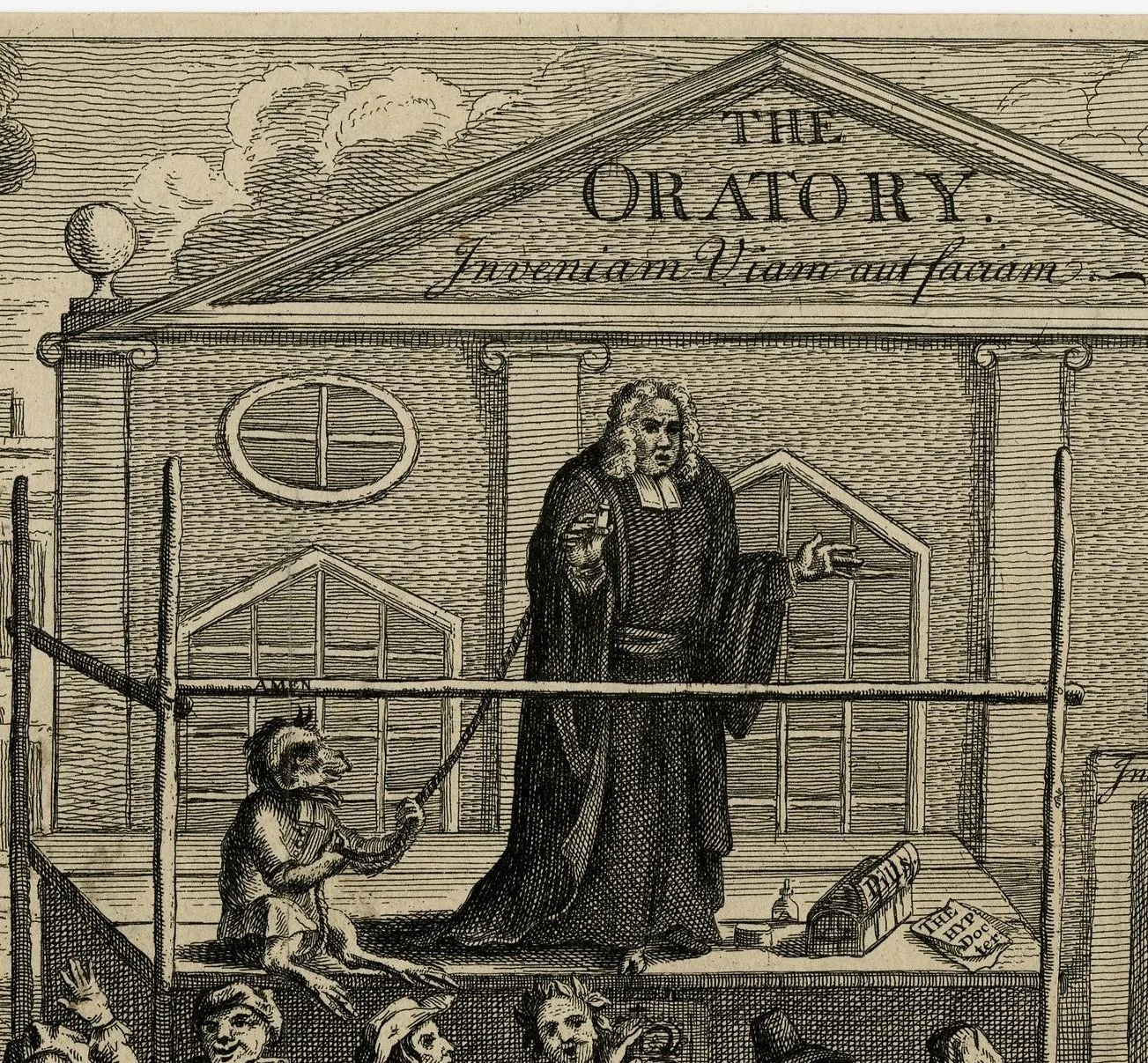

This post is about a graphic satire showing us what graphic satires were surely intended to do: make people laugh. The Oratory (1731), by George Bickham the Younger, depicts laughter of the side-splitting, doubled over, point and jeer variety, laughter that revels in the humiliation it dishes out to its victim, who, in this case, was John ‘Orator’ Henley (1692-1756) [Figure. 1].

John Bickham the Younger, The Oratory (1731). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Henley was an eccentric, a brazen self-publicist, and one of eighteenth-century London’s most noted oddities. He turned his hand to many things. The Orator was a school master, clergyman, scholar, journalist, and a paid informer for Robert Walpole’s spy network, passing information about his fellow hacks to the government that helped it to squeeze the opposition press. From 1730 he published The Hyp-Doctor, a pro-Walpole weekly that served as a loyalist antidote to The Craftsmen, though far clumsier. Henley’s betrayal was surely why his fellow hacks savaged him so keenly. But he also made himself an easy target. Henley had a high opinion of his intellect – he published Spanish, French, Italian, Greek, Latin, and Hebrew grammars, all of them poor – and of his piety. Frustrated that the Church of England would not give him a seat he felt worthy of his talents, in 1725 he resigned his position at St Mary Abchurch and set up his own dissenting ministry, The Oratory, in Newport Market, the butcher’s quarter of London. [1]

The Ego had landed. In addition to the Sunday sermon, Henley’s congregation was subjected to a theological lecture every afternoon, an academic (and often political) oration each Wednesday evening, and the celebration of his own version of the primitive liturgy once a month. Each event was advertised in the Saturday papers a week in advance, and each showcased Henley’s excruciating brand of elocution, which combined gurning, exaggerated hand gestures, hyperbole, and wildly unpredictable diction. Henley told anyone who would listen that he had recovered the purity of primitive Christianity, but contemporary satirists felt that his ministry was little more than the ugly, incoherent ramblings of a deluded loudmouth who routinely overstretched his limited abilities – ‘Orator’ was an ironic nickname. If Henley had another brain, satirists suggested, he’d still only be a half-wit.

Detail 1. Henley as a quack.

Detail. 2. Paying to worship (background).

Bickham depicts Henley in full flow, preaching on a platform outside his oratory unaware that all around conspires to mock him. This conceit was a pun on The Hyp-Doctor and presents The Orator as a quack flogging worthless treatments on a stage (note the bottle and pills at his feet) [detail. 1]. The joke was simple – Henley’s ministry, like a mountebank’s quackery, is a scam – and responded to a real feature of the oratory, Henley’s charging his congregation to hear him, as shown on the right of the print where a man pays his entrance fee at a toll booth inside the building (‘The Treasury’) [detail. 2] [2]. The effrontery of selling the gospel appalled contemporary opinion, but the hubris of the medals Henley sold to his regulars astonished. The medals bore Henley’s motto, ‘Inveniam viam aut faciam’ (‘I shall either find a way or make one’), words spoken by Hannibal before he crossed the Alps, and which were inscribed above Henley in The Oratory [Fig. 2]. Satirists jeered that comparing Hannibal’s achievements in leading the Carthaginian army across a mountain range to invade the Roman Republic with the establishment of a tinpot chapel in a London meat market was an act of outrageous self-importance. At the top-left of the print, modesty turns tail and flies away for shame.

Figure 2. One of the medals Henley issues to his congregation. Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum. M.8232

The Oratory paraded Henley as a fool. An ape on the left of the stage holds him on a leash – The Orator is a monkey’s performing monkey. He is also a fool’s fool, shown by the group of men in the foreground, labelled ‘Ha’, ‘He’, ‘Te Hee’, ‘He’, and ‘Silly Cur’, who laugh at his oration, and by the puritan to their right, who turns down Henley’s ‘Scout’, having finally found a sermon he is prepared to miss [detail. 3]. Folly, seen in a coach at the top left of the print, prefers to give Henley a wide berth too, heading instead for more stimulating company at the Dunce’s Cap inn. One of the group of fools is Colly Ciber, the Poet Laurette and actor who was widely mocked for butchering the tragedies – even this buffoon was able to jeer at Henley. [3] The man at the bottom left of the scene is more direct. He shits on some of Henley’s publications and uses others to wipe his arse.

Detail 3.

The print’s aggression is palpable. Why? Because Henley was dangerous (to his enemies, at least). He may have been an ignoramus who pretended to be a scholar, a braggart who pretended to be pious, but he was a man who coarsened public debate and who had a platform and that gave him an influence that must be checked [4]. Laughter controlled. Making Henley a buffoon ensured he could not be taken seriously. One opposition newspaper, The Connoisseur, tried to do so:

the Clare-Market Orator, while he turns religion into farce, must be considered as exhibiting shews and interludes of an inferior nature, and himself regarded as a Jack-pudding in a gown and cassock

But The Oratory suggested that he was villainous, too [5]. A cloven hoof shows from beneath his robe, and ‘Merit’ is inscribed next to the gallows at the left of the print. But even hanging, the verses below suggest, would be too much time wasted on Henley:

O! Orator, with brazen face and lungs;

Whose jargon’s formed of ten unlearned Tongues;

Why Stand’st thou there awhole long hour haranguing

When half the time fits better Men for hanging?

Bickham wants us to laugh at Henley and then ignore him. The humiliation is akin to execution in effigy.

Few prints portray laughter, which is why I was so taken with The Oratory. But what was this brutal laughter doing? The many explanations of why we laugh can be group together under three headings: the superiority, incongruity, and relief theories of laughter [6]. All three theories agree that we are moved to laugh by something surprising or unexpected. But they differ in their approach to the psychological causes and social effects of laughing. Superiority theories see laughter as aggressive, malicious, and belittling. We laugh at something or someone that we feel is inferior to us, and which we find contemptible (sexist, racist, or stereotypical jokes fall into this category, as does mockery). Laughing reinforces discrimination and stokes feuds and conflict. Incongruity theories see laughter as benevolent. We laugh when we encounter something out of the ordinary that delights us (slap stick, puns, and surreal comedy fall into this category). That laughter is a mark of fellowship and binds friendship and social groups. Finally, relief theories argue that laughter releases pent up aggressions or tensions that might otherwise be expressed in violence or disorder (social or psychological). Research tends to assess those theories in either/or terms and tries to establish which one best explains the instance of laughter being studied. What graphic satires like The Oratory show us, however, is that each act of laughter involves elements of all three theories.

This becomes clear once we unpick the context of this print. Henley may have been the most mocked man in London. But the attack in The Oratory was more specific and had grown out of a spat between Henley and Alexander Pope that was subsequently extended in the Hyp-Doctor and The Grub Street Journal. The story begins with Pope, who had included Henley in his hacks’ fools’ gallery, The Dunciad (1729). Henley is one of a chorus of modern writers who read but don’t understand, gobbling up acres of print then spewing it back out undigested:

There, dim in clouds, the poreing Scholiasts mark,

Wits, who like Owls see only in the dark,

A Lumberhouse of Books in ev’ry head,

For ever reading, never to be read.

But, where each Science lifts its modern Type,

Hist’ry her Pot, Divinity his Pipe,

While proud Philosophy repines to show

Dishonest sight! his breeches rent below:

Imbrown’d with native Bronze, lo Henley stands,

Tuning his voice, and balancing his hands.

How fluent nonsense trickles from his tongue!

How sweet the periods, neither said nor sung!

Still break the benches, Henley! with thy strain,

While Kennet, Hare, and Gibson, preach in vain. [7]

Oh great Restorer of the good old Stage,

Preacher at once, and Zany of thy Age!

Oh worthy though of Egypt’s wise abodes,

A decent Priest, where monkeys were the Gods! [8]

But Fate with Butchers plac’ thy priestly Stall,

Meek modern faith to murder, hack, and mawl;

And bade thee live, to crown Britannia’s praise,

In Toland’s, Tindal’s, and in Woolston’s days…..

(The Dunciad, Book 3, lines 186-208).

The mock-heroic tone shatters Henley’s self-importance. Pope pictures The Orator doused in the excrement of modern pot philosophy that squats above him. Suitably inspired, Henley then preaches in a pompous, deluded manner, convinced that he is a superior rhetorician to some of the finest churchmen of his time (White Kennet, Francis Hare, and Edmund Gibson) when in truth he butchered piety in a butcher’s yard.

The Dunciad infuriated Henley. His account of his own life – published under the pseudonym Nicholas Welstede – defended himself and counter-attacked, a theme that he returned to regularly in the Hyp-Doctor (and no doubt in his oratory) [9]. In response, The Grub Street Journal (a paper that was essentially a Dunciad-in-miniature, lampooning many of the hacks close to Walpole’s regime) resumed Pope’s assault [10]. The edition of 13 May 1731 responded to Henley’s criticism of a previous essay that had called him ‘The Hero of Impudence’. Didn’t the label fit? The Grub Street Journal asked, in mock surprise. Hadn’t Henley publicly challenged the great and the good of church and state to debate him, who knew nothing? Hadn’t he libelled bishops by name, while preaching meekness and charity? And didn’t his grammars prove that he was ignorant of learning? The bulk of the essay focussed on that theme, listing Henley’s linguistic errors with glee. It concluded thus:

Is not My Henley the Hero of Impudence? Why then should he be angry with me? Is it not […] a noble and glorious title? After the publication of his Grammars, he erected his Oratory […] He then by himself, or by his friend, gave the world an account of himself; pointing at several persons as his adversaries in print: tho’ some of them, at least, (and it may be true of the all, for all I know) never wrote a line about him in their lives; and would have thought it much beneath them to have employ’d one single quarter of an hour on so vile a subject.

The joke? Henley deserved to be chastised but writing about a man so base shamed satirists and cheapened satire:

It is indeed the only difficulty we labour under with regard to such as He is (if ever there were such another) that tho’ they ought (for the public good) to be chastised, yet we are heartily asham’d to chastise them, or have anything at all to do with them [….] this Creature is a public nuisance: in every thing but outward shape, a monstrous production; a species by himself….

The verses inscribed in Bickham’s The Oratory followed at the end of the edition. Graphic satire extended mockery from one medium into another. It kept the joke running.

How do we explain this laughter? It was certainly prompted by incongruity – the overblown motto, a man controlled by an ape, a hack too stupid for folly. And it was driven by superiority – Henley is treated with contempt, shat upon, laughed at by fools and, Bickham expects, sneered at by the viewer. But there was something else at work here. The Oratory was aggressive. Its laughter didn’t relieve, or act as a substitute for, violence but was the real thing, intending to wound Henley and damage his reputation. It was the work of a bitter emotion – spite. The print was concerned with the pettiness that festers in feuds, the nasty joy of malice and one-upmanship. This gives us pause for thought. Satires like The Oratory tend to be studied as ‘political prints’. It would certainly be easy to read it as such, to see its denigration of Henley as an attack on the government of his patron, Walpole, or to present it as yet another indictment of corruption in the Robinocracy. But The Oratory’s laughter was more personal than political, more intimate than ideological. It was about settling scores. Graphic satires like this offer us a way into the history of emotion and the history of laughter. Those histories are as human as History can be. But they are also often ugly.

1. On Henley, see Graham Midgely, The Life of Orator Henley (Oxford, 1973), from which this section is drawn.

2. The doorman is a butcher, a joke on the lowly place of Henley’s Oratory. The theme was common in ridicule of Henley.

3. Cibber was a favourite target of The Grub Street Journal. He was also accused of corruption and his appointment as Poet Laurette was the subject of much scorn.

4. This reminds me of antipuritan criticisms of puritan preachers common since the 1580s, the fear that the ignorant were being given platforms above their station. Dissenting ministers were often mocked in this way. It is unfair on Henley though, who was educated (he had a degree from Cambridge). He was no scholar, but neither was he a tub preacher.

5. This became a theme of later attacks on Henley. He became known as a loud and belligerent drinker in London’s taverns. His criticism of the government also became more violent after the fall of Walpole in 1742. He railed against corruption, describing England as ‘Hanoverian Pig-Style’ in 1754. He was arrested for a sermon on St Andrews Day (30 November) 1746, suspected of sedition for the tone of his criticism of the government’s reprisals against the Jacobites after the ’45 Rebellion. Prints of that year made much of this. He was discharged by the King’s Bench on 19 June 1747.

6. See the introduction to Mark Knights and Adam Morton, eds, The Power of Laughter and Satire in Early Modern Britain, 1500-1820 (Boydell and Brewer, 2017).

7. White Kennet, Bishop of Peterborough (died 1728); Frances Hare, Bishop of Chichester; Edmund Gibson, Bishop of London (and the leading churchmen of Walpole’s government). Gibson was a Whig in politics, but High Church in religion. Hare had begun to lean towards the High Church by 1731, too.

8. There are a series of long footnote on Henley in The Dunciad. Book III, n.195 notes that ‘this man had an hundred pounds a year given him for the secret service of a weekly paper of unintelligible nonsense’. It gives a long extract from ‘Welstede’s’ life of Henley, mocking his self-importance and Henley’s claims that his failures in the world were the result of the meanness of others rather than his own folly. Henley’s view that he was the ‘Restorer of ancient Eloquence’ is also mocked in the notes. Pope also makes a series of accusations that Henley denied (that he offered to be a pen for hire and had been prosecuted). ‘He turned his Rhetorick to Buffoonry upon all publick and private occurrences. All this passed in the same room; where sometimes he broke Jests, and sometimes that Break which he call’d the Primitive Eucharist’.

9. See, for instance, The Grub Street Journal no. 88.

10. The Grub Street Journal was sponsored, in part, by Pope. It attacked many of those mentioned in The Dunciad as well as those, like Colley Cibber and Stephen Duck, who were loyal to the Hanoverians. For previous assaults on Henley see, for example, 29 April, which mocks his history of his life.